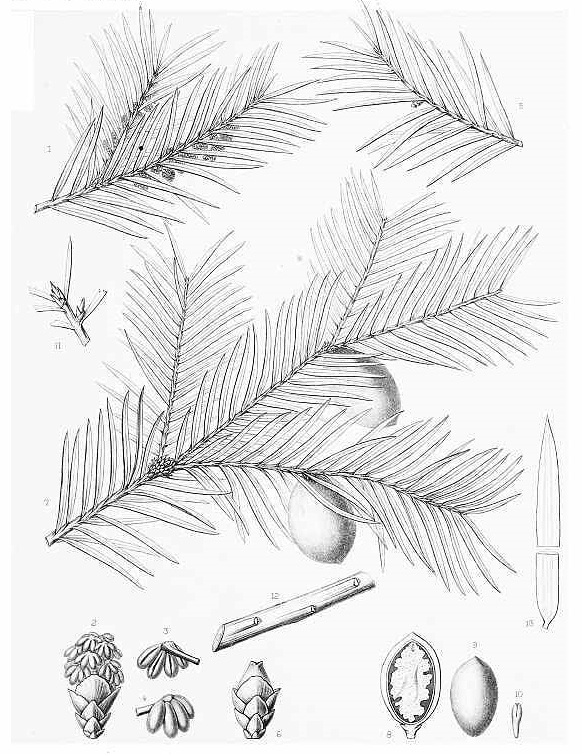

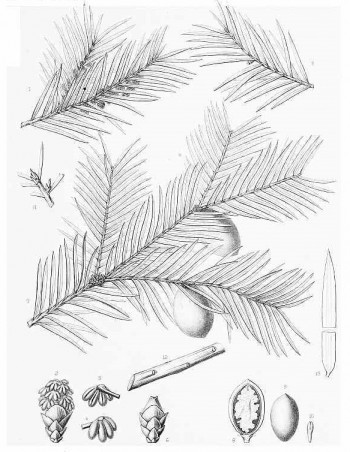

Torreya taxifolia, the type species of the genus Torreya, was described in 1838 by the Scottish botanist George Arnott Walker-Arnott (1799-1868), in Annals of Natural History, 1st edition. It was discovered in 1833 by Hardy Bryan Croom (1797-1837) near the Aspalaga Crossing on the Apalachicola River in Florida. The epithet taxifolia means "leaves like Taxus (yew)." Other species in the genus have leaves that are significantly longer than those of most yews, but the description was fortuitous, for the other species were named after this one was already described. Its common names include Florida nutmeg-yew, gopherwood, and stinking cedar. The latter name refers to the strongly fetid odor released when its leaves or seed cones are crushed.

Description. Florida nutmeg-yew is an evergreen coniferous species of tree which may reach mature heights of 40 to 65 feet (12 - 20 m) tall with a trunk 12 to 20 inches (30 - 50 cm) in diameter at breast height. It has a rather open, conical crown and whorled branches, which are spreading to slightly drooping.

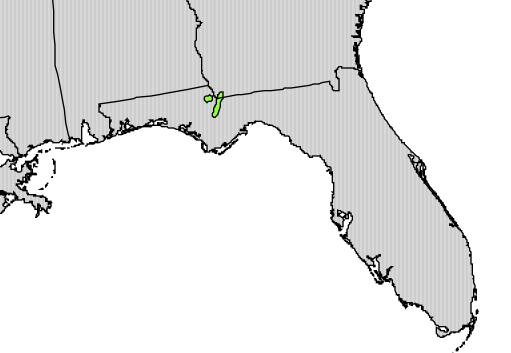

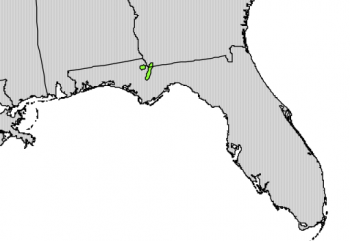

Distribution. Torreya taxifolia is an endangered species which grows naturally in only three counties in Florida - Gadsden, Liberty, and Jackson. It is also found in southern Decatur County, Georgia, just north of Chattahoochee, Florida. The natural range of this species extends along the limestone bluffs for a 40 mile (64 km) stretch on the eastern bank of the Apalachicola River and its tributaries from Chattahoochee south to Torreya State Park in northern Liberty County, Florida. One additional population exists approximately 7 miles (11 km) west of the Apalachicola River in the vicinity of Ocheessee Pond in Jackson County, Florida. It grows on river bluffs, deeply shaded slopes, and moist wooded ravines at elevations of 50 to 100 feet (15 - 30 m) above sea level, frequently in association with its rare cousin Taxus floridana, as well as Fagus grandiflora, Liriodendron tulipifera, Ilex opaca, Acer barbatum, Pinus taeda, Pinus glabra, and Quercus alba. The climate in this part of the Florida Panhandle is warm and humid, with a wet summer and a dry autumn and winter. The growing season averages 270 days (April 1 to September 30), with average rainfall during that time of 32 to 34 inches (810 - 860 mm). Total annual rainfall averages 56 inches (1,420 mm). The average January temperature is 54°F (12°C), while the average July temperature is 81°F (27°C). Occasional cold snaps during the winter bring a minimum temperature of 15° to 20°F (-9° to -7°C). A low of -2°F (-19°C) has been recorded in Tallahassee, Florida, 40 miles (64 km) east of the Apalachicola River.

This species is a rare endemic. The current wild population is estimated to be between 500 and 600 trees. Of these less than 10 are known to produce seed cones or pollen cones. Most stands persist as immature stump sprouts, less than 6.5 feet (2 m) tall. No wild trees are considered to be more than 35 years old. Before the start of the decline in the early 1950s, the wild population was estimated at more than 600,000. The primary reason for this massive decline is infection of the trees by fungi which cause stem and needle blight. Though up to 11 species of fungi attack Torreya taxifolia, the worst offenders appear to be Physalospora spp. and Macrophoma spp. Investigators have not precisely determined how fungal agents act to cause the blight. Fungicide treatment (Maneb), frequently applied, has shown to provide some control of the condition, with renewed vigor and unblemished new growth at the results. If Florida nutmeg-yew is to be preserved, it will be necessary to isolate and propagate blight-resistant trees. A number of diseased specimens up to 30 feet (9 m) in height are to be found at Maclay State Gardens, Florida. There are 14 disease-free individuals at the Biltmore Estate, Asheville, North Carolina that are over 40 years old and up to 40 feet (12 m) tall, but they are not thought to be blight resistant. However, those specimens could and should be used to provide seeds and cuttings for the development of disease-free stock for restoration efforts.

An interesting theory which purports to explain the very limited native range of this species (unrelated to current pathogenic problems) is as follows: Recovery of the species may be inhibited by postglacial warming, as it is better adapted to the cooler, moister climate found in its native range during the last ice age. As the climate warmed, the species may not have been able to move northward due to poor dispersal abilities. Some biologists have suggested that Torreya taxifolia was originally dispersed by a now-extinct animal. Its seeds are extremely hard and require some scarification to germinate, which may have been accomplished by passing through an animal's digestive tract. The terpene content of the fleshy fruit and the thinness of the seed's shell imply that the ecological partner may have been a large tortoise.

Ethnobotany. Wood of this species is finely grained and is light, strong, and durable. Historically, that wood was utilized for fence posts, shingles, furniture, and as fuel for riverboats. It has at times been planted as a landscape specimen in and around Tallahassee, and one such specimen has achieved 30 feet (9 m). Some larger specimens are being grown elsewhere in botanical gardens, which is where this species has the best chance of survival. The champion specimen is in North Carolina, having attained a height of 45 feet (14 m) and width of 40 feet (12 m). The Atlanta Botanical Garden has an active propagation program for this species for conservation purposes, and an organization dedicated to relocating the species has been planting specimens in the southern Appalachians.