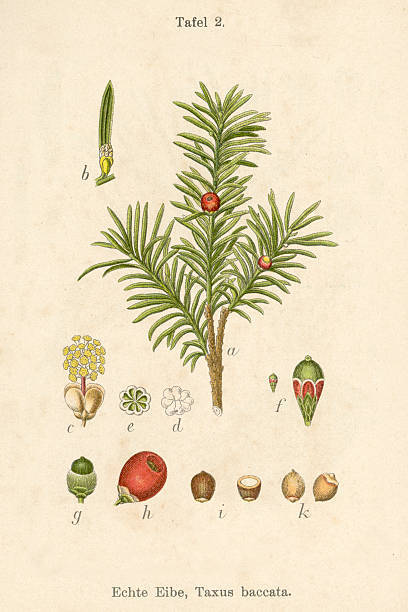

Taxus baccata, as described in 1753 by Carolus Linnaeus (1707 - 1778) in Species Plantarum, is commonly known as European, English or common yew in the English language; as well as Eibe in German; If in French; Tasso in Italian; and Tejo in Spanish. It is the type of the yew genus. The species name describes the seed cones (arils), Latin for "berry-like."

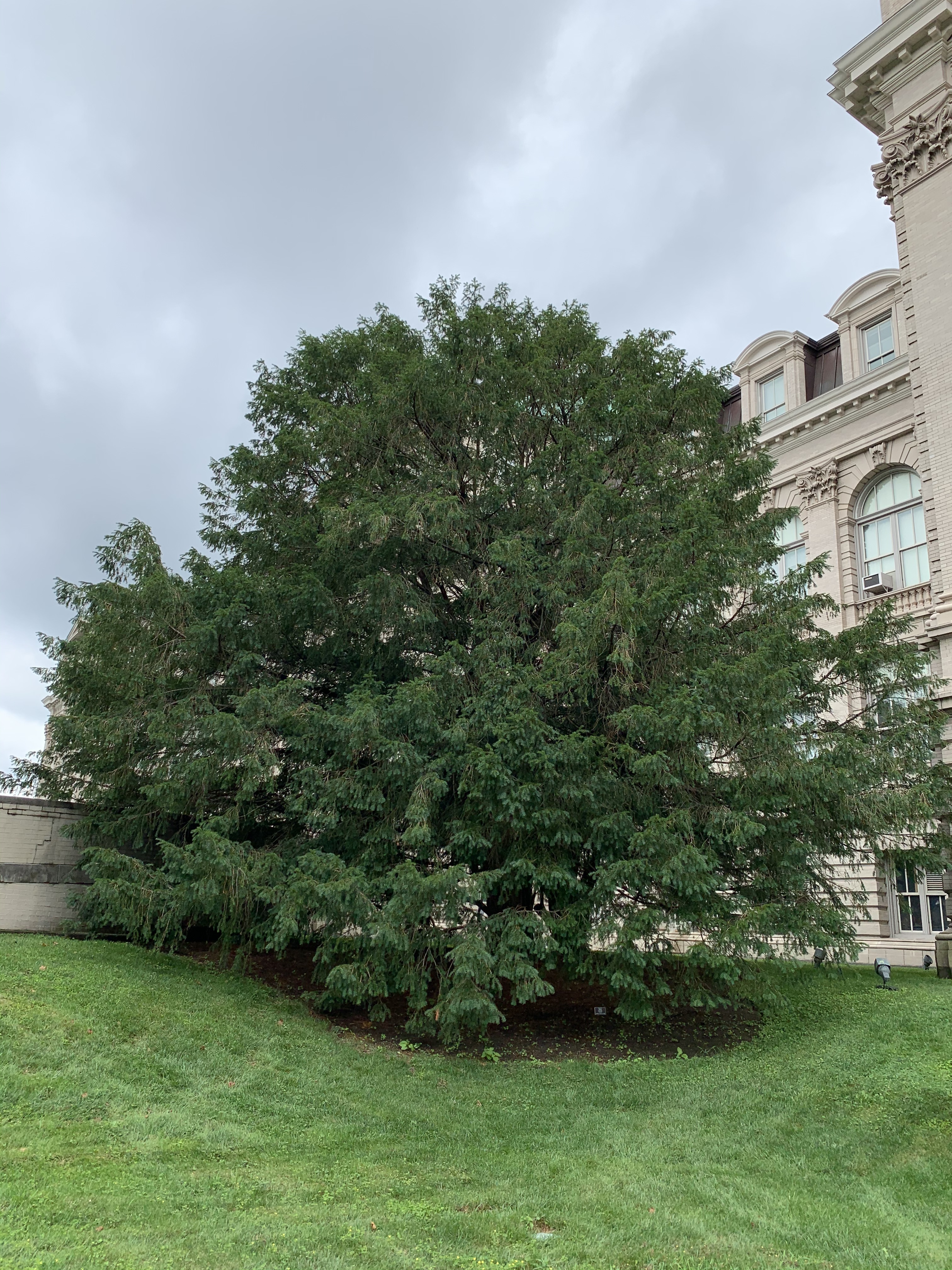

Description. English yew is an evergreen, mostly dioecious, coniferous tree that grows to mature heights of 30 to 60 feet (10 - 20 m) tall, occasionally to 120 feet (40 m) tall with a trunk up to 12 feet (4 m) in diameter, measured at breast height. The crown is normally pyramidal, becoming irregular with age; but many cultivated forms depart dramatically from this.

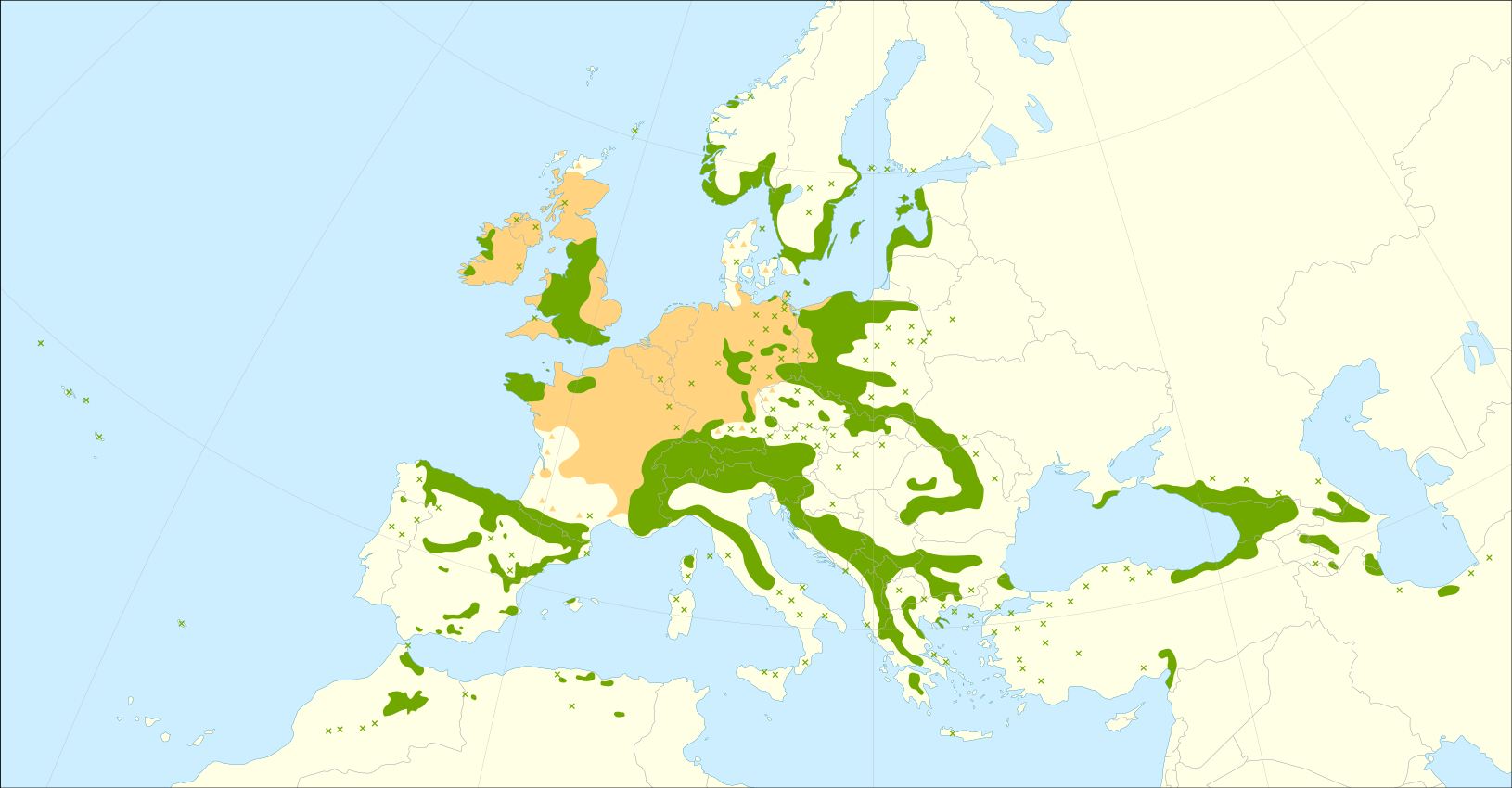

Distribution. This species is native to nearly all of Europe, from northern United Kingdom south through northern Africa and east into western and southern Turkey to the southern shores of the Caspian sea, growing as individuals or small groves in mixed forests near streams or on moist slopes with a limestone substrate. In the Mediterranean, it is known to exist only in the mountains.

Hardy to USDA Zone 6 - cold hardiness limit between -10° and 0°F (-23.2° and -17.8°C).

Taxus baccata has played a major role in several religious traditions. This may have occurred because the tree is poisonous, valued for a variety of medicinal purposes, and symbolic of eternal life due to its "evergreen-ness," exceptional longevity, and the wood's resistance to decay. Thus the tree unites death (by poison) with eternal life, a concept well explored by Laqueur (2015). The Greeks wove funeral wreaths from it in honor of Hecate, whose dominion was death. The Celts used its wood for for votive and funerary artifacts, planted it in their holiest shrines (or perhaps chose its groves to site those shrines), and attributed to it a host of magical properties memorialized in their folklore. Following conversion of the Celts to Christianity, many of the Celtic shrines were appropriated as sites of churches and other Christian shrines, and ancient yews resident at these locations were preserved - perhaps to further legitimize the new religion. Whatever the reason, this cultural preservation of ancient yews accounts for the existence of the oldest and largest known individuals. Account by Hal Hartzell Jr. from his 1991 book, The yew tree: a Thousand Whispers. Eugene, Oregon: Hulogosi Press.