Juniperus virginiana, as described in 1753 by Carl Linnaeus (or Carolus Linnaeus) (1707-1778), in Species Plantarum, 2nd edition, is commonly known as eastern red-cedar, red-cedar, eastern juniper, red juniper, pencil cedar, or aromatic cedar. In its native range it is commonly called "cedar" or "red-cedar;" names that are rejected by the American Joint Committee on Horticultural Nomenclature as it is, in fact, a juniper, not a true cedar (Cedrus). However, "red-cedar" is the most-used common name.

There are two specific varieties, which intergrade where they meet:

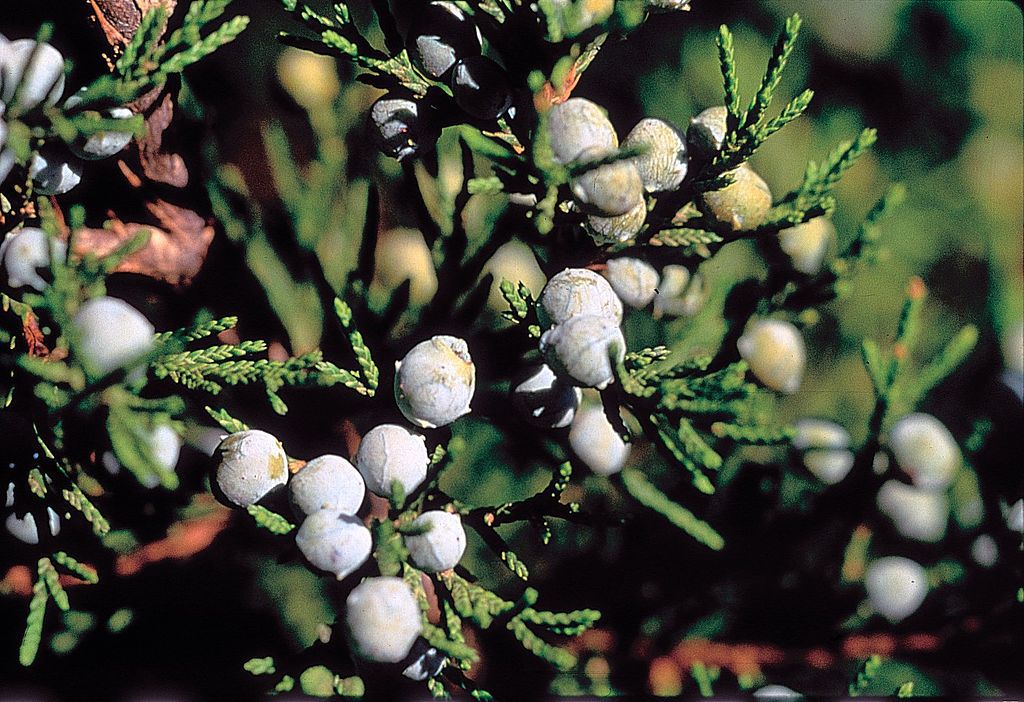

Description. Eastern red-cedar is a densely branched, slow-growing evergreen coniferous species of tree that may never become more than a bush on poor soil, but ordinarily grows to mature heights of 15 to 60 feet (5 - 20 m) or rarely to 90 feet (27 m) tall, with a short trunk, 12 to 40 inches (30 - 100 cm) or rarely to 70 inches (170 cm) in diameter at breast height. One of the oldest reported trees, from Missouri, was 795 years old.

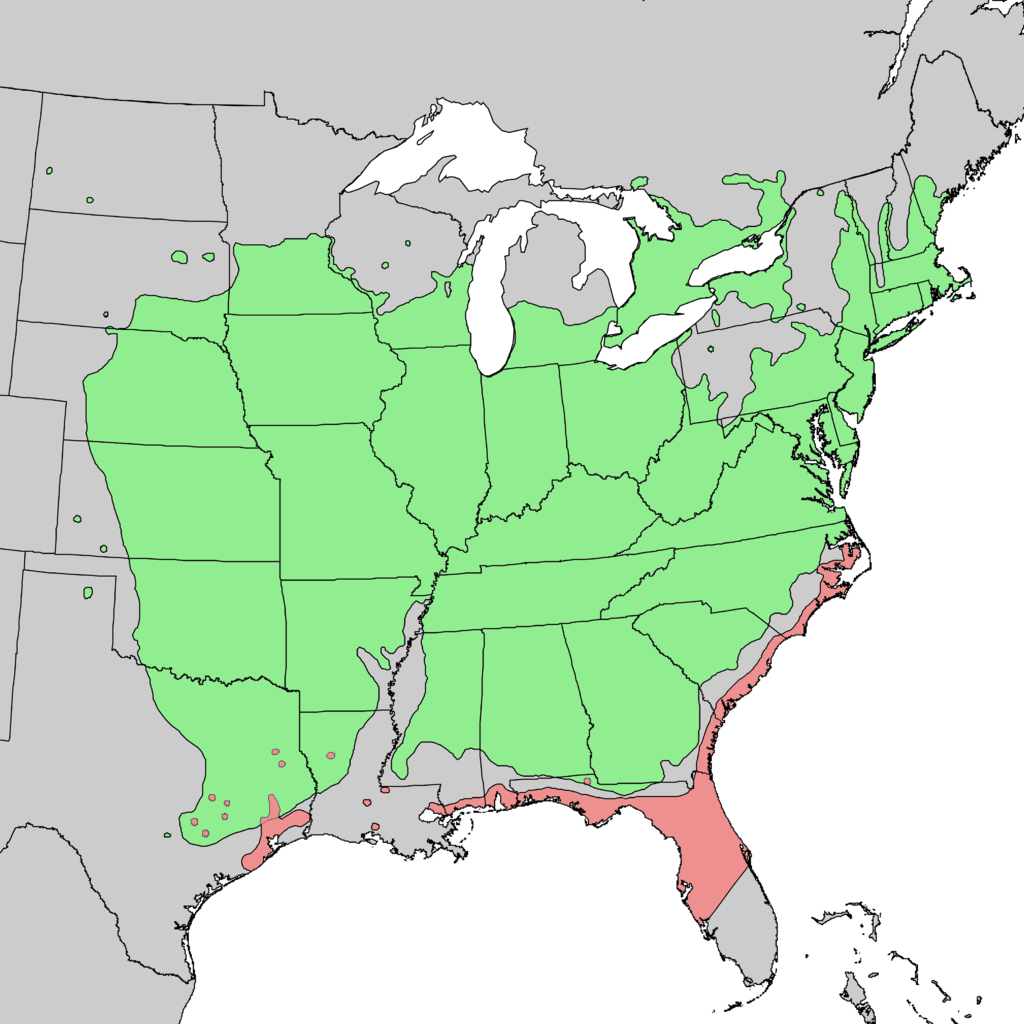

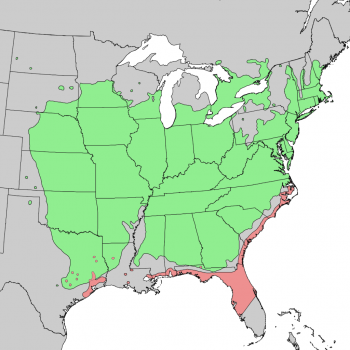

Distribution. This species is native to Canada - Ontario and Québec. In the USA - Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin; naturalized in Colorado and Oregon. Further west it is replaced by the related Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) and to the southwest by Ashe juniper (Juniperus ashei).

Hardy to USDA Zone 4 cold hardiness limit between -20 and -30ºF (-28.9 and -34.4ºC).

It is a pioneer invader, which means that it is one of the first trees to repopulate cleared, eroded, or otherwise damaged land. It is unusually long lived among pioneer species, with the potential to live over 850 years. The tree is commonly found in prairies or oak barrens, old pastures, or limestone hills, often along highways and near recent construction sites. It is an alternate host for cedar-apple rust disease, an economically significant disease of apples, and some management strategies recommend the removal of J. virginiana near apple orchards.

In many areas the trees are considered an invasive species, even if native. The fire intolerant J. virginiana was previously controlled by periodic wildfires. Low branches near the ground burn and provide a ladder that allows fire to engulf the whole tree. Grasses recover quickly from low severity fires that are characteristic of prairies that kept the trees at bay. With the urbanization of prairies, the fires have been stopped with roads, plowed fields, and other fire breaks, allowing J. virginiana and other trees to invade. Trees are destructive to grasslands if left unchecked, and are actively being eliminated by cutting and prescribed burning. The trees also burn very readily, and dense populations were blamed for the rapid spread of wildfires in drought stricken Oklahoma and Texas in 2005 and 2006.

Damage done by J. virginiana includes out-competing forage species in pastureland. The low branches and wide base occupy a significant portion of land area. The thick foliage blocks out most light, so few plants can live under the canopy. The needles that fall raise the pH of the soil, making it alkaline, which holds nutrients such as phosphorus, making it harder for plants to absorb them. Juniperus virginiana has been shown to remove nitrogen from the soil after invading prairies. It has also been found to reduce carbon stores in the soil. This reduction in soil nutrients also reduces the amount and diversity of microbial activity in the soil.

During the Dust Bowl drought of the 1930s, the Prairie States Forest Project encouraged farmers to plant shelter belts (wind breaks) made of eastern juniper throughout the Great Plains. They grow well under adverse conditions. Both drought tolerant and cold tolerant, they grow well in rocky, sandy, and clay substrate. Competition between trees is minimal, so they can be planted in tightly spaced rows, and the trees still grow to full height, creating a solid windbreak in a short time.